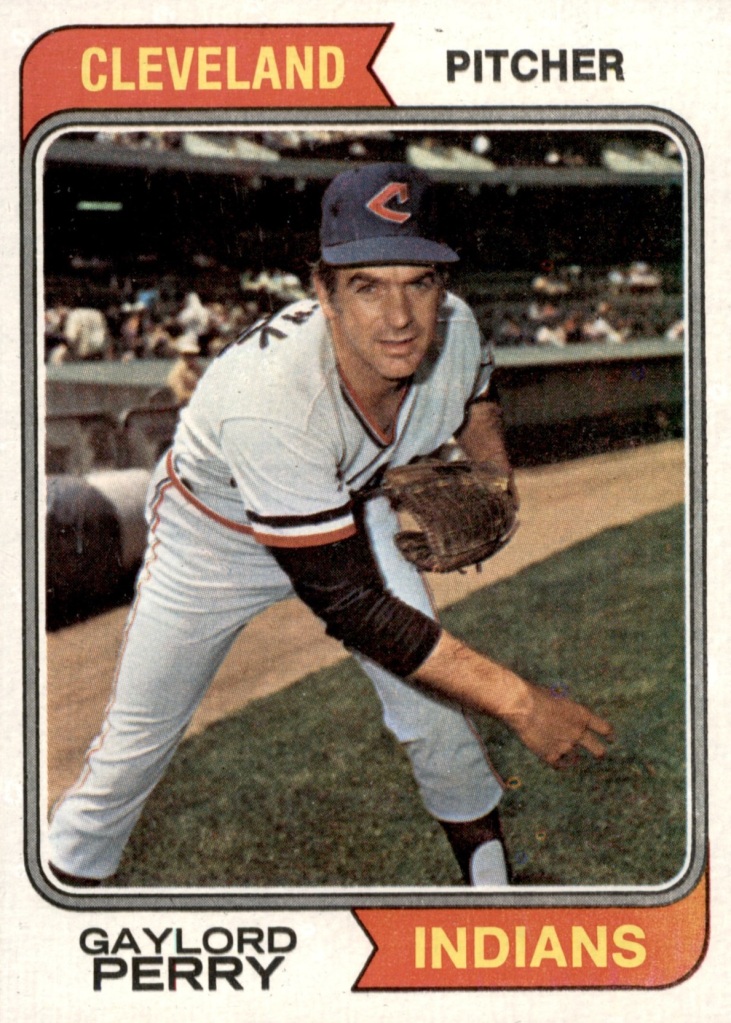

Gaylord Perry passed away yesterday at age 84. The Hall of Famer played 22 years for eight teams, winning 314 games, earning two Cy Young Awards, and sparking endless conversations about his propensity to load up the baseball with Vaseline. He learned the pitch in 1964, three seasons into what was to that point a pedestrian career, from Giants teammate Bob Shaw, and used the pitch for the next two decades to great effect, in the process becoming one of the sport’s most colorful figures.

Given that The Baseball Codes devoted an entire chapter to cheating, Perry’s presence loomed large in the book. Here, in his memory, is an excerpt of the most noteworthy passage.

In April 1973, Yankees outfielder Bobby Murcer exploded to the press after facing Cleveland’s greaseball king Gaylord Perry in the pitcher’s second start of the season, yelling: “Just about everything he throws is a spitter. . . . The more he knows you’re bothered by him throwing it the better he is against you. He’s got the stuff behind his ear and on his arm and on his chest. He puts it on each inning. I picked up the balls and they’re so greasy you can’t throw them.” Murcer went so far as to call commissioner Bowie Kuhn “gutless” for refusing to respond—and this was after the outfielder had recorded a three-hit game against Perry. When the pitcher was confronted with Murcer’s accusations, however, he said that Murcer hit “fastballs and sliders,” not spitballs. It would have been a more credible excuse had Perry been on the same page as his catcher, Dave Duncan, who in a separate, contrived denial said that Murcer had hit “off-speed stuff.”

To further the argument, The New York Times hired an unnamed Yankees pitcher to chart Perry’s every pitch throughout the game, marking those he thought to be spitballs. When the resulting pitch chart was compared with a replay of the game, the Times noted that, before every pitch identified as a spitter by the Yankees operative, Perry tugged at the inside of his left sleeve with his right (pitching) hand—an action he did not take for the rest of his repertoire. Yankees second baseman Horace Clarke, according to the chart, struck out on a spitter that, on replay, was seen to drop at least a foot. In the fourth inning, Thurman Munson asked to see the ball twice during his at-bat—during which, said the chart, Perry threw four spitters.

But Perry wasn’t just a practiced spitballer—he was also a practiced spitball deceiver. One of the strengths of the pitch, according to virtually everybody who has been suspected of throwing it, is that making a hitter believe it’s coming is nearly as valuable as actually throwing it. “The more people talk and write about my slick pitch, the more effective I get,” wrote Perry in his autobiography, Me & the Spitter. “I just want to lead the league in psych-outs every year.” To this end, Perry turned into his era’s version of 1950s spitball artist Lew Burdette—all fidgets, wipes, and tugs once he stood atop a mound.

“Perry’s big right hand started to move and people started to boo,” wrote Gerald Eskenazi in the Times, about its charted game. “First he touched his cap, sliding his fingers across the visor, bringing them down along the right side of his head, stopping behind his ear. Then the hand went across his uniform, touching his chest, his neck. Was all this to create a diversionary action? Was he simply having fun? . . . ‘I did the same things I always did,’ Perry said later, suppressing a smile. ‘If people want to read things into it, so be it.’ ”

Partly in reaction to the uproar Perry caused, a rule was implemented in 1974 that removed the mandate for hard proof in an umpire’s spitball warning, saying that peculiar movement on a pitch provided ample evidence. It didn’t take long—all of six innings into the season—before Perry earned his first warning under the new rule. Not that it mattered; by the end of the season he had won twenty-one games, was voted onto the All-Star team, finished fourth in the Cy Young balloting, and was thrown out of exactly zero games for doctoring baseballs.

It wasn’t until 1982, when Perry was forty-three and in his twenty-first season in the big leagues, that he was finally disciplined for loading up a baseball, when he earned a $250 fine and ten-day suspension after throwing two allegedly illegal pitches as a member of the Mariners—the first such punishment for this type of activity since Nelson Potter in 1944. By that point, Perry had become the most frequently accused spitballer in big-league history, and did little to dispel the notion: Not only was his autobiography suggestively titled, but it came out in 1974, nearly a decade before he retired; his North Carolina license plate read SPITTER; when his five-year-old daughter was asked by a TV reporter in 1971 whether her daddy threw a greaseball, she quickly replied, “It’s a hard slider.”

Although Perry claimed, upon his book’s release, that he didn’t throw the spitter any more, Twins manager Gene Mauch was quick to respond, saying, “But he doesn’t throw it any less, either.”

In 1991, after 314 wins over twenty-two seasons, Perry was inducted into the Hall of Fame. George Owens of the Utica Observer-Dispatch described the ceremony: “When Rod Carew was inducted into baseball’s Hall of Fame, Panamanian flags waved. When Ferguson Jenkins was inducted, Canadian flags were flown. When Gaylord Perry was inducted, it began to rain.”

Thank you for reminding us of the great additions to the English language baseball players, managers, reporters and Perry’s daughter are renowned for. He leaves behind many good memories. Happy Holidays.