Trevor Bauer seemed to have it all figured out. He spent years haranguing Major League Baseball about its substance-abuse problem—the substance in question being pine tar and other, more powerful tack—that enables pitchers to increase spin rate to astronomical degrees. He went so far as to write about it in the Players’ Tribune.

When baseball effectively ignored him, Bauer announced publicly that he would try the tactic himself, for an inning in April 2018, and found immediate success.

When baseball continued to not give a shit, the right-hander adopted the practice whole hog last year, winning a Cy Young Award and $100 million over three seasons from the Dodgers.

Bauer’s stated plan: Continue to tack up for as long as baseball ignores it, and stop once effective policing begins. Which is what he wanted in the first place.

Accordingly, details came down over the weekend about MLB’s new stance toward pitcher tack, and the policy, if reports are accurate, seems to have teeth.

According to ESPN’s Buster Olney, proposals include eight-to-10 random checks of pitchers per game, with starters being checked at least twice as they depart the field so as to minimize disruption. Position players might also be checked, though not in so prevalent a fashion. Current penalties involve 10-game suspensions, which are still on the table.

Those who pay attention to such things could see this coming. Earlier this season MLB confiscated a number of balls from one of Bauer’s starts. In May, umpire Joe West took Giovanny Gallegos’ cap due to a discoloration on the brim. This week, Sports Illustrated published a cover story calling sticky stuff “The new steroids,” and hitters across the league have been speaking out on the topic.

Are pitchers paying attention? Let’s turn back to Bauer, who yesterday faced Atlanta with what we can assume to be a diminished supply of sticky stuff on his person. The tell: Entering the game, the average spin rate of Bauer’s four-seam fastball was 2,835 RPM; yesterday he averaged only 2,612 RPM.

Between 2017 and 2019—the seasons prior to what appears to be to be Bauer’s headfirst dive into stickiness—his spin rate climbed from 2,227 to 2,410. Yesterday’s diminished numbers were still significantly higher than that. Does this indicate the right-hander is still using tack, only not as heavily or as frequently as before? Could be. Also noteworthy: Since 2019, Bauer has all but abandoned his changeup, which spins the least of any of his pitches, and which he once considered a useful tool against left-handed batters.

This was all in evidence yesterday, when Bauer yielded three runs on six hits over six innings. It was the most hits he’s allowed this year, and tied for the most earned runs. Notably, Bauer also issued four walks, double his season average, while striking out seven, less than his season average. Opponents had hit .150 against him on the year; yesterday, Atlanta batters hit .250.

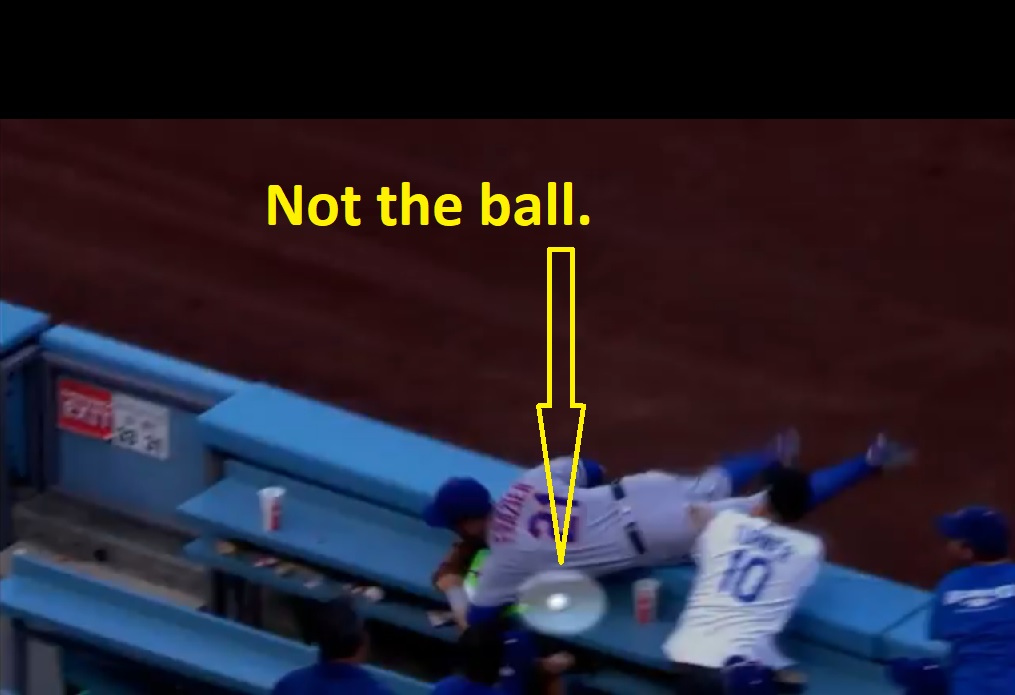

Also, Bauer had at least occasional trouble finding the zone.

Afterward, reporters brought up the topic of sticky stuff with the pitcher. “I’ve made a lot of public comments,” Bauer replied. “If you want to go research it and make your own decision, go for it.” When asked about the cause for the RPM drop, the pitcher was cagey in his response: “I don’t know. Hot, humid day in Atlanta.”

This is the reason most pitchers give for adding illegal tack. In humidity, as well as in cold weather, gripping a baseball becomes more difficult, and pitchers—those who admit to it, anyway—say that an extra dollop of pine tar or the like can help bring them back to normal. For a guy like Bauer, it can help transform a 4.48 ERA in 2019 to a 1.73 ERA in 2020.

Bauer’s hardly alone. On Thursday, Gerritt Cole—who appears to be a personal target of Bauer, and who has been named in court about this stuff—allowed five runs over five innings against the Rays. His spin rate was down across the board, especially on his fastball, which dropped from 2,552 RPM on the season to 2,436. (In 2017, Cole’s last year in Pittsburgh, his four-seam spin averaged 2,164. His first season with Houston he improved that by about 200 RPM. The following year he improved it again by a similar amount.)

Bauer and Cole, of course, are merely two prominent representatives of a widespread practice that has driven offense into a hole. This season, major leaguers are hitting a collective .237, a development that nobody apart from active pitchers can fully embrace.

“I just want to compete on a fair playing field,” Bauer said yesterday, in an Orange County Register report that contains a host of vibrant quotes. “I’ll say it again. That’s been the point this entire time.”

Should Trevor Bauer become human again, that’d be just fine—so long as the rest of baseball’s superman pitchers do, too.