This is what it looks like when things snowball. Wednesday night, after the Mets intentionally walked a batter to face him, Dodgers outfielder Yasiel Puig connected for a monster home run, then stood frozen for several long beats to admire it. This should not have come as a surprise. It is what Puig does.

Still, it rankled numerous Mets. As Puig rounded first base, Wilmer Flores had some words for him. Puig turned around, mid-trot, incredulous, offered a quick Fuck you¸ then slowed his trot to a virtual crawl, his 32.1 seconds rounding the bases being the second-slowest time recorded this season. Catcher Travis d’Arnaud offered some additional thoughts as Puig crossed the plate. (We’ve seen that act before, notably when then-Braves catcher Brian McCann literally blocked the baseline to give Carlos Gomez an earful under similar circumstances in 2013.)

What set the Mets’ response apart, however, was what happened after the inning, when New York’s Jose Reyes and Yoenis Cespedes tracked Puig down in the outfield to deliver a protracted screed about appropriate behavior on a baseball diamond.

“I don’t think he knows what having respect for the game is,” Flores told reporters after the game. “I think there’s a way to enjoy a home run. That was too much.”

“Run the bases,” said Reyes in a Newsday report. “Don’t stand up, then walk four or five steps, then run slow. Wow.”

There are many things to unpack here.

What was the anger about, really?

Puig’s tendency to showboat is maddening for many opponents, but it’s also consistent. His display against the Mets, though hardly unique, may have been spurred to excess, at first by the preceding intentional walk, then by Flores’ comment.

Still, Puig is a central character in the mainstreaming of this type of display over recent years. And he’s hardly breaking new ground, either with his actions or in the types of response they solicit.

In 1977, Puig’s homer-pimping forebear, Oscar Gamble, admired a shot against the Yankees for so long that even before he’d even left the box New York catcher Thurman Munson told him, “All right, now you’re going to get drilled.” (The threat was empty; Gamble was not hit in any of the teams’ five remaining games that season.) Several years later, while playing for the Yankees, Gamble did it again, this time against Baltimore. Instead of threats, he—like Puig on Wednesday—was talked to by members of the opposition. “Eddie Murray and some of them other guys came up to me and said, ‘All right now, you’re taking a little too long up there,’ ” said Gamble, looking back. “That’s respect for players. They let you get your little style points in there, and then you have to go on and do what you do.”

Gamble’s displays were influenced by Reggie Jackson, whose coup de grace came in 1981, during a home run trot against Cleveland’s John Denny. Earlier in the game, Denny had thrown a pair of pitches up and in to Jackson before striking him out. When Reggie homered in his next at-bat, he showed his displeasure by pumping his fist toward the pitcher, then moving excessively slowly around the bases and tipping his cap as he trotted. Denny offered an earful for the duration with such invective that when Jackson crossed the plate, instead of heading back to the Yankees dugout he instead turned toward the mound, sparking an all-out fracas. (Among the peacemakers was Gamble, who literally helped lift Jackson over his head and carry him from the field.)

Jackson was himself influenced by one of the great sluggers of the 1960s, Harmon Killebrew, who was likely the first ballplayer to so admire his own handiwork. All of which is to say that Puig is not exactly breaking new ground, here.

Are the Mets angrier about their own play than about Puig?

After the game, Puig hardly seemed like man who had gained insight, saying, “If that’s the way [Flores] feels, it might be a result of them not playing so well.”

It’s harsh but accurate. The Mets, losers of six of their last seven, sat at 31-40, 11.5 games back in the NL East, and had lost three straight to Los Angeles by a combined score of 30-8 while surrendering a dozen homers. Annoyances are more tolerable while winning than they are while doing whatever it is the Mets have done this year.

“It’s frustration from everyone,” Reyes admitted later.

At least Puig is consistent. The Mets, who entered the season with postseason dreams, are not.

Is a lecture better than a fastball to the ribs?

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of the exchange was the discourse in the outfield between Puig, Cespedes and Reyes.

Cespedes, after all, is a poster child in his own right when it comes to showboating. For him to deliver a lecture on the subject indicates no small amount of transgression on Puig’s part. According to Reyes, Puig had no idea what was on the Mets’ mind when the New York duo tracked him down in the outfield.

“He didn’t even know what he did,” Reyes told reporters. “He continued to say to me and Cespedes, ‘What did I do? What did I do wrong?’ Wow. If you don’t know what you did wrong, you’ve got problems.”

Puig was so unable to handle the heat that he did not even look at Cespedes while his countryman grew increasingly animated during the conversation. Instead, he looked at Reyes, standing silently nearby. When it came time for Reyes to speak, he kept his message simple. “Man, you have to be better than that,” he told Puig. “You have to make people respect you as a player.”

It’s a noble notion, but to judge by early results, it didn’t take.

“[Cespedes] told me to try to run a little bit faster and gave me some advice,” said Puig in a New York Post report. “I don’t look at it that way.”

Is it a cultural divide?

Much has been written about players from Latin America and the stifling nature of baseball’s unwritten rules. Let players have fun out there has become a regular refrain on baseball blogs, and it’s not entirely wrong. The ability to distinguish exuberance from disrespect is vital when it comes to integrating increasing numbers of foreign players into America’s pastime.

But when Puig says things like this …

We are not understood. We have to adapt. There are things we are not used to doing in our countries. When you keep doing things wrong, people get tired; I even got tired myself. There should not be so many rules. You just have to do your job and let people have fun, which is what I was doing in 2013. They’ve wanted to change so many things about me that I feel so off. I don’t feel like the player I was in 2013.

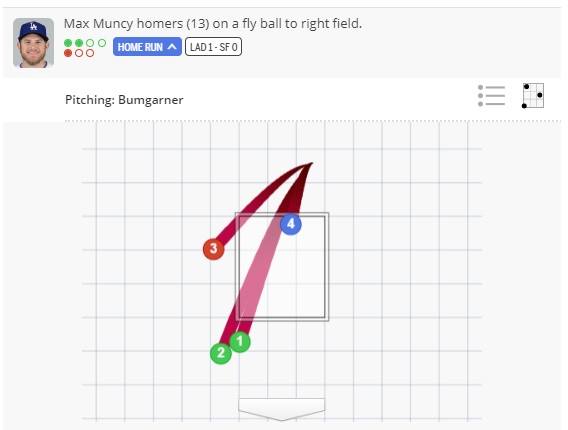

… it feels like an excuse. He has gone from the runner-up Rookie of the Year in 2013 to a guy the Dodgers have been actively shopping for multiple seasons now. His batting average has dropped from .319 to its current .244. Even though Puig is on pace to set a career high in homers (he currently has 13), his slugging percentage and OPS are far below what they were during his first two campaigns. He has been consistently injured, and was even farmed out to Triple-A Oklahoma City for a month last year. This is not simply a matter of his team stifling his celebratory nature.

In fact, it’s worth asking whether the opposite might be true. Might Puig, without the onslaught of attention for his bat flips and home run watching, without the lectures from opponents and teammates alike, without the array of distractions caused by his own on-field behavior, maybe be a better player than he currently is?

The question is unanswerable, unless Puig himself proves it one way or another.

What are we left with?

Strip everything else away—the caveats about internal frustration and Puig’s established behavior and all the prior precedence—and the lone question remaining is, Were the Mets right to get upset?

The answer is yes. The answer is yes because Puig’s display on Wednesday was not about exuberance or about some unknown entity trying to stifle his essential nature. The answer is yes because Puig had malice aforethought in everything he did during the play. He was pissed that the Mets walked Joc Pederson to face him. He was pissed because Flores scolded him at first base, and d’Arnaud did it again at the plate. His action was intended to show the Mets up, and that’s exactly how the Mets took it. Puig wasn’t celebrating, he was gloating.

It’s the difference between the first historic example above, in which Oscar Gamble was wrapped up in the wonder of being Oscar, and the second, in which an angry Reggie Jackson could not find enough ways to display his loathing of the opposition.

There is a distinction, and it is important. On Wednesday, the Mets understood it. To judge by his reaction, Puig never will.

Following up

Following up