By handing down a seven-game suspension to Amir Garrett, Major League Baseball has thoroughly muddied the waters about what it wants to see from players when it comes to celebrations.

On Saturday, Garrett punctuated a strikeout of Anthony Rizzo by yelling at the batter, a one-on-one confrontation taken by those in the Cubs dugout as disrespectful. It’s not difficult to understand where they were coming from. It was disrespectful. So disrespectful that Javy Baez vaulted the dugout railing and charged the field.

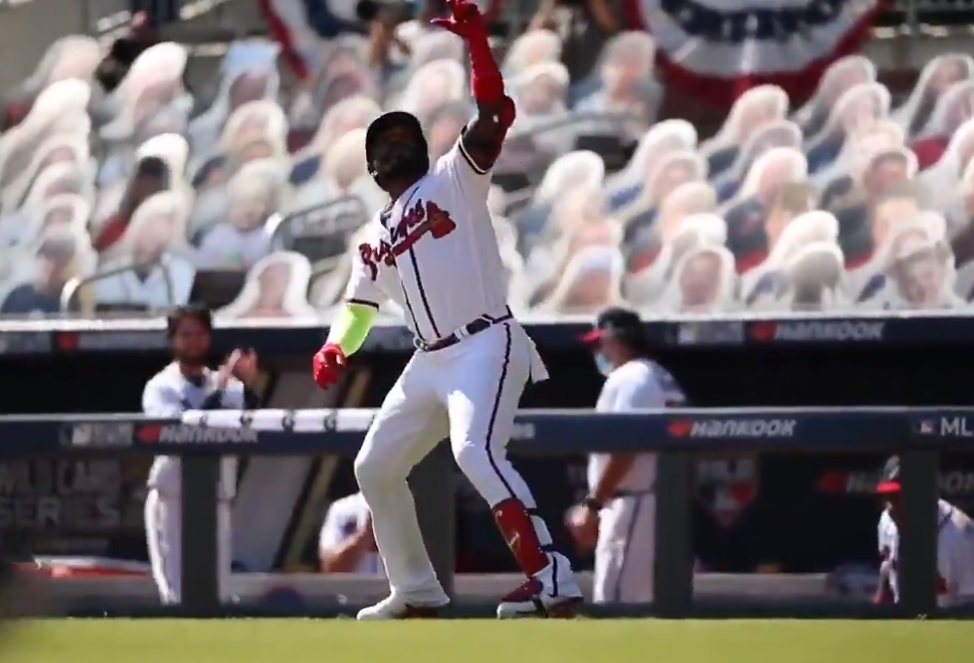

Given that Garrett was subsequently suspended for seven games and Baez only ended up with a fine, MLB is clear in who it holds culpable. Except that Garrett didn’t put anybody in danger; the physical confrontation was prompted by Baez. MLB ruled similarly earlier in the month when it suspended Nick Castellanos for flexing over pitcher Jake Woodford, punishment that would have almost certainly been absent had not Yadier Molina reacted by pushing Castellanos from behind. For that, Castellanos was suspended for two games while Molina got off scott free.

Garrett’s suspension leads to a question similar to those raised following the Castellanos incident: Had Baez not responded, and had Rizzo returned to the dugout as he was already doing, would the league have handed down any discipline at all? Not damn likely.

So we’re left to guess. Bat flips have recently gone mainstream, in no small part because the league officially adopted them as part of its play-up-the-personalities campaign. A decade ago, however, they were seen as disrespectful. Had an incensed opponent charged the field in response to one, who would the league have held to account? According to the current structure, it’d be the bat flipper himself.

At least the decision to suspend Garrett more or less lines up with the way players see things on the field. Pitchers mostly don’t take offense to bat flips, and hitters mostly do take offense to being yelled at after they strike out. That’s because what Garrett did is genuinely offensive, and bat flipping is not.

People keep talking about how reactions like Garrett’s and Castellanos’ are standard fare in the NBA, and wonder why baseball so breathlessly tries to tamp down such behavior. There are a few reasons for this. For one thing, short of starting a fight there’s no such thing as retaliation in the NBA—not in the sense of a pitcher throwing at a hitter, anyway. Also, action waits for no man, and there’s not much time during a basketball game to consider somebody’s words. Guys can jaw all they want, but by the time the guys they’re insulting have formulated a response they’re already heading back down the floor. In the NFL, end-zone dances have become commonplace, but teams continue to get flagged for taunting should they cross that particular line.

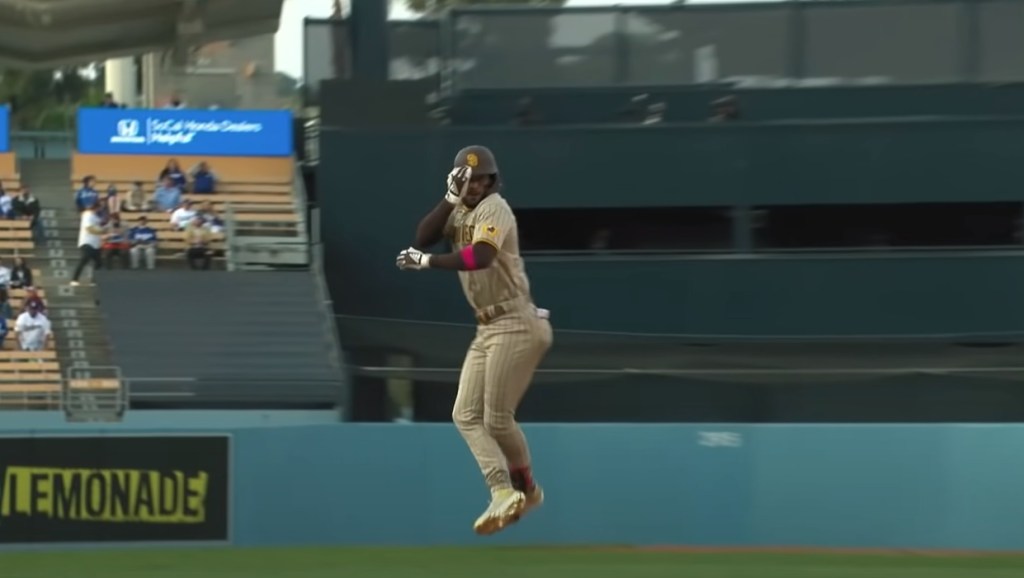

What MLB wants here is obvious: Feel-good celebrations that can be marketed to a baseball-centric crowd. Even Garrett’s own “rock the baby” motion, which he does after getting a big out—putting the opponent to sleep or whatnot—has not been taken too personally by opponents.

What MLB does not want is just as obvious: A turn toward the NBA. How do we know? Because if this was really about guys stoking dangerous situations, then the players responsible for physical confrontations—Baez and Molina, respectively—would be punished in ways similar to or exceeding the revelers. That didn’t happen.

The league office has spoken, so listen up. Keep it clean, baseballers, and celebrate at your own pace so long as you stay on the proper side of the league-designated line.

And if by chance you don’t know where that line is drawn, they’ll be sure to tell you.