Ray Fosse passed away yesterday after a 16-year battle with cancer. The thing is, nobody in Oakland knew anything about it until August, when, facing renewed assault from the disease, the ex-catcher could hide it no longer and had to step away from his broadcast duties for the team. Even his colleagues had no idea. I last spoke to Ray in June for a feature I was writing, and he offered no clue about having to endure what must have been a considerable personal struggle.

I’ve listened to Fosse on A’s broadcasts since the 1980s, and got to know him while researching Dynastic, Bombastic, Fantastic: Reggie, Rollie, Catfish, & Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s. I traveled around the country to interview most of the team’s players for the book, but not Ray, who was happy to repeatedly carve out time for me before games at the Oakland Coliseum. Over the course of that summer I found myself repeatedly headed to the ballpark to hunker down for 30 or 45 minutes in Ray’s office, talking about the good old days.

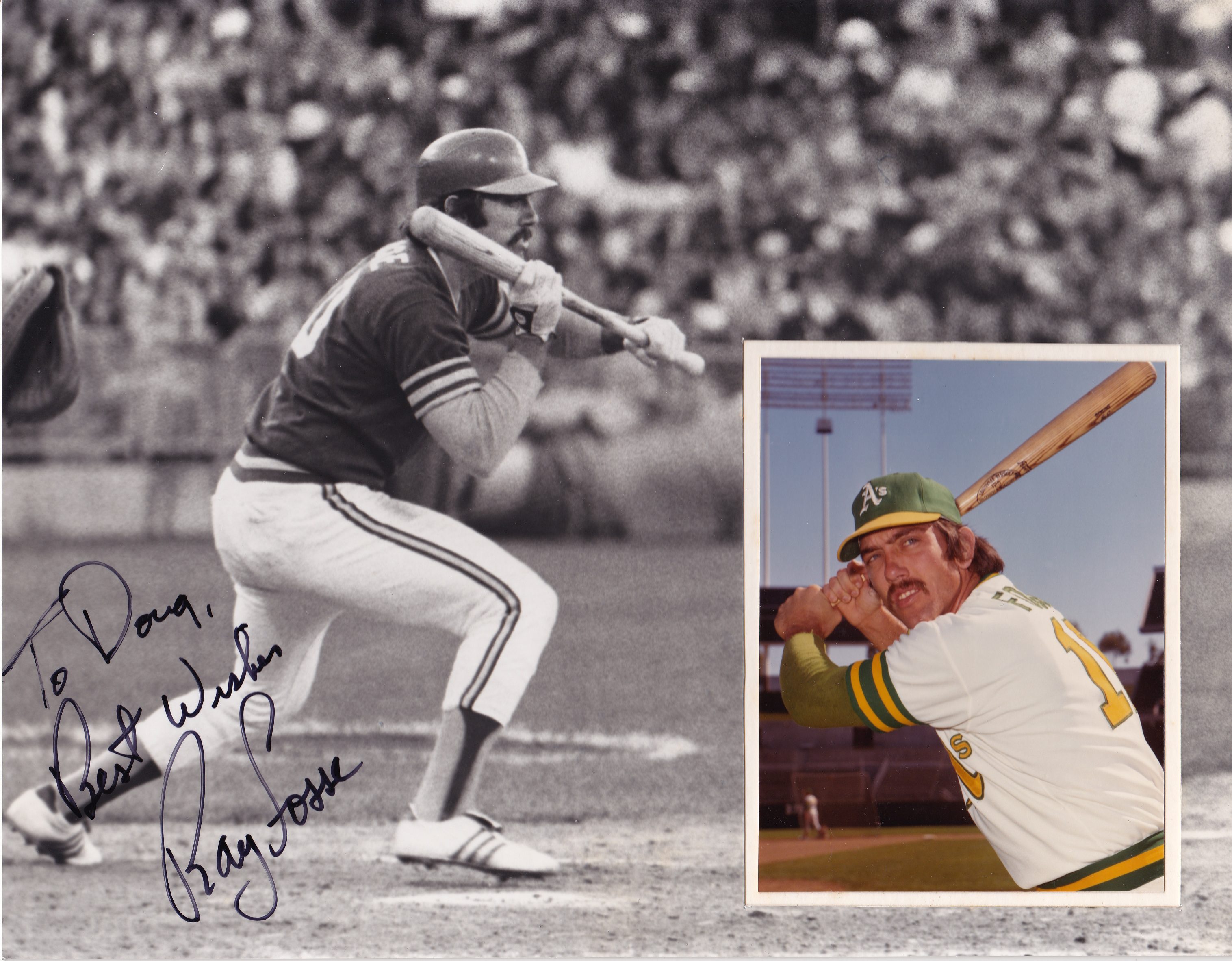

Fosse was an interesting cat. He played in the big leagues for a decade and was a two-time All-Star. He won a pair of World Series with the A’s, but is best known for the collision with Pete Rose during the 1970 All-Star Game that resulted in a separated shoulder that hampered him through the rest of his career.

From Dynastic:

As a prep, the Marion, Illinois, native had turned down Bear Bryant’s pitch to play football at the University of Alabama in favor of baseball at Southern Illinois. Fosse was eventually selected seventh overall by Cleveland in the first-ever player draft in 1965, six slots after the A’s took Rick Monday. A power hitter with a rocket arm, he won Gold Gloves and made All-Star appearances his first two full seasons, in 1970 and 1971. The most notable moment of his career, however, was also its least fortunate. During the 1970 All-Star Game in Cincinnati, with the score tied 4–4 in the bottom of the 12th inning, Pete Rose decided to win the game in front of his hometown fans. Taking off from second base on Jim Hickman’s single, Rose didn’t break stride around third. The throw home from Royals center fielder Amos Otis sailed wide, forcing Fosse several steps up the third-base line to field it. Rose led with his left shoulder as he barreled into Fosse, knocking the catcher backward and sending the ball ricocheting toward the third-base dugout. Rose scored, the National League won, and Fosse said his shoulder “felt as though it had been mangled.” When X-rays came back negative, Fosse, despite being unable to raise his left arm, opened the second half behind the plate for Cleveland, batting cleanup. The catcher, who collected 16 homers and 45 RBIs before the injury, accounted for only two and 15, respectively, in the second half. The following April, eight months after the injury, further X-rays detected the fracture through which Fosse had been playing.

Fosse ended up being an excellent defensive catcher for many years to come, but was never able to recapture the hitting touch he lost in that collision.

That wasn’t Fosse’s only notable injury. While helping to break up a clubhouse fistfight between Reggie Jackson and Billy North in June 1974, he was thrown backward into a locker partition and ended up with injuries to his C6 and C7 vertebrae, which impacted a nerve in his throwing shoulder. Misdiagnosed at first as having a separated cervical disc, he spent a week in traction at Merritt Hospital, 20 hours per day with a strap wrapped around his jaw and neck, pulling his head upward in an effort to alleviate pressure on his spine. Then he took six weeks off, hoping to heal naturally. Then he had surgery—which he scheduled himself at UCSF—to fix the problem.

After coming back that August, Fosse batted .185 with only one homer in 32 games. This led to one of my favorite comeback stories from those A’s teams. Charlie Finley wanted to omit Fosse from the playoff roster against Baltimore, but manager Alvin Dark, understanding the importance of a stout defensive presence, was adamant about his inclusion. (In the three months Fosse spent on the disabled list Oakland’s team ERA was 3.21; after he came back, it was an even 2.50.)

Fosse responded by hitting a game-sealing homer (after having already singled and doubled) in Game 2, which the A’s won behind a complete-game shutout from Ken Holtzman. (Notably, Holtzman’s 2.19 ERA when Fosse caught was nearly two points lower than it was with everybody else.)

This set the scene for the postgame press conference. From Dynastic:

After the game Fosse was shepherded to a media session in the exhibition hall between the Coliseum and the adjacent Coliseum Arena, home to the NBA’s Golden State Warriors. As usual, the Owner did his darndest to turn it into The Charlie Finley Show, bursting into the room and screeching, “Yeeeeeeah, Fosse—that’s my boy,” almost as soon as the questions for the catcher had begun. In his hand was a glass that had until very recently been filled with champagne. Once every head in the room had spun his way, Finley enthused, “It wasn’t the bat, it was the Fosse that swung it!” There was no moment, it seemed, beyond opportunity for the Owner to draw attention to himself. Fosse was incredulous. “Then why didn’t you want to play me from the beginning?” he yelled. It was an instinctive response. Finley didn’t even bother to answer. He didn’t have to. He’d already taken what he wanted.

The A’s won their third straight championship that season (and their second with Fosse). Finley sold him back to Cleveland after the 1975 campaign.

Fosse had worked on A’s radio broadcasts since 1986, and on their TV broadcasts since 1988. He will be missed by Bay Area baseball fans, and especially so by those who got to know him even a little.

Baseball lost a good one yesterday.