What looked to become a full-blown confrontation yesterday in Scottsdale was quickly defused when Jason Heyward, at the plate for the Cubs, informed an increasingly agitated Madison Bumgarner that he was shouting not toward the mound, but at his own teammate, Dexter Fowler, standing atop second base.

Heyward had just struck out looking on a terrific breaking pitch, and appeared to be frustrated with … something. But why was he yelling at Fowler? The obvious conclusion is that he had received a signal for the upcoming pitch, and that the intel Fowler provided was incorrect. (Watch it here.)

If that was the case, of course, the only thing wrong with the scenario was Heyward’s inability to wait until he and his teammate were off the field to express his displeasure. Coming as it did in the middle of a freaking game, the outburst managed to draw some attention.

“They might want to be a little more discreet about that if you’re going to do that kind of thing,” said Bumgarner afterward in the San Jose Mercury News.

Which is the thing. MadBum, perhaps the game’s premier red-ass, was entirely unwilling to abide Heyward shouting something at him from outside the baseline, but when it came to stealing signs … well, they should have been a little more discreet.

Pinching a catcher’s signals from the basepaths and relaying them to the hitter is an ingrained part of baseball culture. Teams don’t like having their signs stolen, of course, but the most frequent reaction is not to get angry, but simply to change the signs.

For his part, Heyward denied the accusation, saying, “He made a great pitch on me, a front-door cutter, and I’m all, ‘Hey Dex, what’ve you got? Ball or strike?’ … There’s no tipping of signs, believe it or not. It wasn’t going on, especially in a spring training game.”

It’s true that it seems silly to steal signs during an exhibition contest, but spring training is used to hone all aspects of one’s game. Heyward is new to the Cubs, and may simply have been trying to dial in his ability to communicate from afar with various teammates. Even if he wasn’t, it sure looked like he was—and that alone is enough place the Cubs under suspicion around the rest of the league.

An entire chapter was devoted to the topic in The Baseball Codes. Here’s some of it, long but worthwhile:

It started with a thirteen-run sixth. Actually, it started with a five-run fifth, but nobody realized it until the score started ballooning an inning later. It was 1997, a sunshiny Wednesday afternoon in San Francisco. By the end of the game, it was 19–3 Expos, and the Giants—the team at the wrong end of that score—were angry, grumbling that the roster of their opponents was populated by thieves.

San Francisco’s thinking stemmed from the belief that it likely takes more than skill or luck to send seventeen men to the plate against three pitchers in a single inning. There was no disputing the numbers: Montreal had six players with three or more hits on the day, and in the sixth inning alone, five Expos picked up two hits apiece, including a pair of Mike Lansing homers. Montreal opened its epic frame with eight consecutive hits, two shy of the big-league record, and it was a half-hour before the third out was recorded.

San Francisco’s frustration boiled over when manager Dusty Baker spied Montreal’s F. P. Santangelo—at second base for the second time in the inning—acting strangely after ten runs had already scored. One pitch later, the guy at the plate was drilled by reliever Julian Tavarez. Two batters later, the inning was over. “They were killing us,” said Baker. “F.P. was looking one way and crossing over, hands on, hands off, pointing with one arm. I just said, ‘That’s enough. If you are doing it, knock it off— you’re already killing us.’ ”

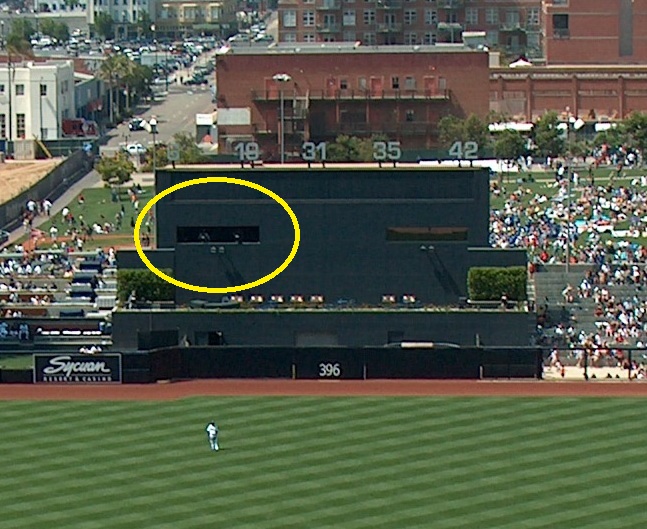

What Baker was referring to was the suspicion that Santangelo and other members of the Expos had decoded the signs put down by Giants catcher Marcus Jensen for the parade of San Francisco pitchers. From second base a runner has an unimpeded sightline to the catcher’s hands. Should the runner be quick to decipher what he sees, he can—with a series of indicators that may or may not come across as “looking one way and crossing over, hands on, hands off ”—notify the hitter about what to expect. Skilled relayers can offer up specifics like fastball or curveball, but it doesn’t take much, not even the ability to decode signs, to indicate whether the catcher is setting up inside or outside.

If the runner is correct, the batter’s advantage can be profound. Brooklyn Dodgers manager Charlie Dressen, who was as proud of his ability to steal signs from the opposing dugout as he was of his ability to manage a ball club, said that the information he fed his players resulted in nine extra victories a year.

Baker sent a word of warning to the Expos through San Francisco third-base coach Sonny Jackson, who was positioned near the visitors’ dugout. Jackson tracked down Santangelo as the game ended and informed him that he and his teammates would be well served to avoid such tactics in the future. More precisely, he said that “somebody’s going to get killed” if Montreal kept it up. The player’s response was similarly lacking in timidity. “I just told him I don’t fucking tip off fucking pitches and neither does this team,” Santangelo told reporters after the game. “Maybe they were pissed because they were getting their asses kicked.”

The Giants’ asses had been kicked two nights in a row, in fact, since the Expos had cruised to a 10–3 victory in the previous game. It was while watching videotape of the first beating that Baker grew convinced something was amiss, so he was especially vigilant the following day. When Henry Rodriguez hit a fifth-inning grand slam on a low-and-away 1-2 pitch, alarm bells went off in Baker’s head. Former Red Sox pitcher Al Nipper described the sentiment like this: “When you’re throwing a bastard breaking ball down and away, and that guy hasn’t been touching that pitch but all of a sudden he’s wearing you out and hanging in on that pitch and driving it to right-center, something’s wrong with the picture.” The Expos trailed 3–1 at the time, then scored eighteen straight before the Giants could record four more outs.

Baker knew all about sign stealing from his playing days, had even practiced it some, and the Expos weren’t the first club he’d called out as a manager. During a 1993 game in Atlanta, he accused Jimy Williams of untoward behavior after watching the Braves’ third-base coach pacing up and down the line and peering persistently into the San Francisco dugout.

For days after the drubbing by Montreal, accusations, denials, veiled threats, and not-so-veiled threats flew back and forth between the Giants and the Expos. Among the bluster, the two primary adversaries in the battle laid out some of the basics for this particular unwritten rule.

Santangelo, in the midst of a denial: “Hey, if you’re dumb enough to let me see your signs, why shouldn’t I take advantage of it?”

Baker: “Stealing signs is part of the game—that’s not the problem. The problem is, if you get caught, quit. That’s the deal. If you get caught you have to stop.”