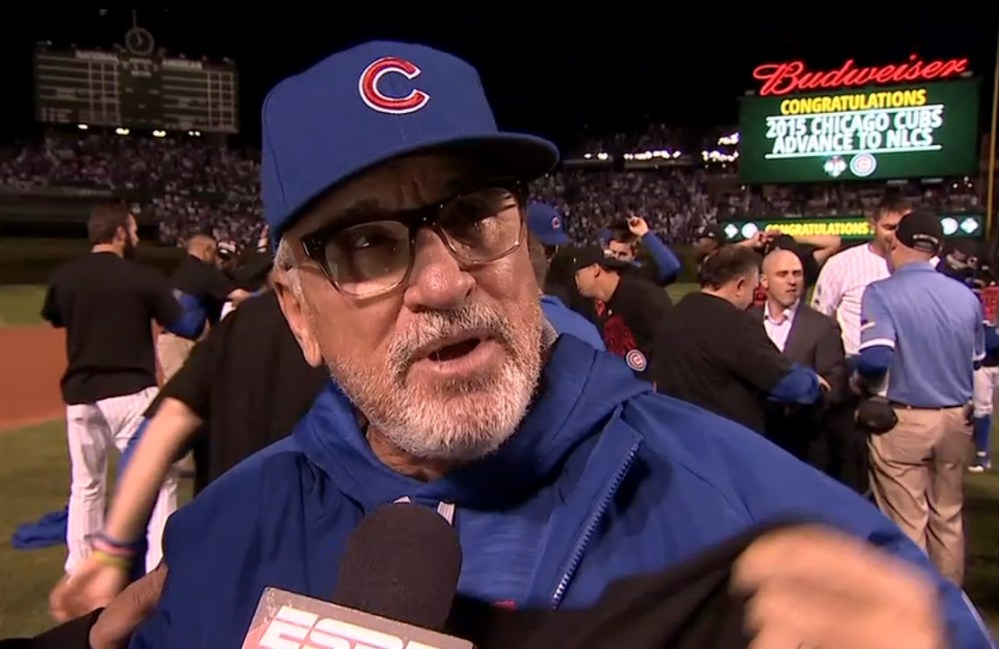

Tony La Russa is one of the most vengeful men baseball has ever known. An entire book, Buzz Bissinger’s “3 Nights in August,” went into great detail about his deliberative process as manager of the Cardinals when it came to figuring out which opponent to have drilled, and when.

On Tuesday, La Russa took a different avenue for retaliation.

It started when Pirates reliever Arquimedes Caminero popped two members of the Diamondbacks in the head—Jean Segura with a 96 mph fastball off the helmet, and Nick Ahmed with an 89 mph splitter off the chin. Both were almost certainly unintentional, and neither player was seriously injured. (In between, Arizona reliever Evan Mashall drilled Pittsburgh’s David Freese on the arm, leading to warnings for both benches, and Caminero’s ejection after hitting Ahmed. Watch it all here.)

In the Pirates broadcast booth, play-by-play man Greg Brown openly discussed La Russa’s history of retaliation, which was already more on the record than any manager in history. La Russa—now Arizona’s chief baseball officer—heard it, and invaded Pittsburgh’s booth to take direct issue. Brown directed the argument away from the microphones so that it would not be broadcast, and then opted against mention it on the air out of respect for La Russa. (Watch Brown discuss the incident here.)

La Russa blew that whole plan out of the water, however, by discussing the incident himself, with AZCentral. His goal was to explain why the Pirates were at fault, any lack of intent on their HBP’s be damned:

“A lot of guys who are pitching in don’t have the ability at this point to command it and it becomes very dangerous,” La Russa said in the article. “The reasoning you get from the other side is they didn’t mean to do it intentionally. If you don’t have command, then that’s intentionally careless.”

He was referring to Pittsburgh’s team philosophy, which has pitchers constantly working the inside edge, and has led the Pirates to leading baseball in hit batters from 2013 to 2015. Diamondbacks broadcasters repeatedly intoned a similar message during the game, decrying what they described as an institutionally reckless approach.

On Wednesday, Diamondbacks manager Chip Hale got right to the organizational talking points, echoing La Russa by telling reporters that Caminero was less at fault for the hit batters than Pittsburgh management.

“I don’t think the kid meant to do it,” he said. “When you put a guy out there that doesn’t have control in that area and you’re trying to pitch in, it’s not something that we can have here. The guy doesn’t have the ability to pitch in certain quadrants of the zone, we don’t do it. It’s almost the fault more of the coaching and the managing than it is the player at that point.”

The D’Backs have some history upon which to build their argument. In 2014, Pittsburgh closer Ernesto Frieri unintentionally broke Paul Goldschmidt’s hand with a pitch. (Arizona responded by drilling Andrew McCutchen in the back.) A year earlier, Pirates starter James McDonald hit Aaron Hill, breaking his hand.

La Russa’s response seems to be a new front in his retaliatory battle. A vengeance fastball to the ribcage might send a message to the opposing clubhouse, but a full-fronted PR battle against an opponent’s organizational philosophy? That’s a new one.

In case anybody doubts La Russa’s intentions, he went on the air with Arizona Sports 98.7 FM on Wednesday morning and discussed the situation further.

“So people are just telling them hey, you can’t just willy nilly throw the ball inside,” he said, via the station’s website. “It’s a real easy formula we’ve used for years: you can’t use us as targets, even if it’s unintentional. If you can’t command the ball inside, don’t throw it up and in — you’ve got to get the ball down. It’s really not that tough, it’s one that we try to enforce, and it’s one I think MLB could be more proactive in enforcing.”

Also, this: “They’ll just keep doing it to you, (and) pretty soon the guy the guy [who keeps getting hit] will not want to go to bat, and how do you win? So you’ve got to use common sense. It’s a competition and guys are going to anything they can to take something away from you.”

Adding that teammates are like family, La Russa said that if somebody slaps one of your family members, “you just slap back.”

Maybe La Russa’s canny, maybe he’s crazy. Maybe he’s both. The sport he loves is changing beneath his feet, moving away from the hard edges of intimidation and retribution, and toward the let’s-make-baseball-fun-again generation of bat flips and promo ops. Whether La Russa is willing to acknowledge these things is almost beside the point. Everything he’s said in recent days is based on inherent truths of competitive sports, regardless of whether the people hearing it agree with him.

The trick now is figuring out how to implement it all within the modern landscape. When it comes to guys like La Russa—at the top of his organizational food chain, who can do pretty much whatever the hell he wants—the question matters less on a day-to-day basis than in big-picture form. That’s why the messages he’s sending seem more a matter of selling the public on his approach. Yep, La Russa and his crew are waging a PR campaign on behalf of a team’s right to drill its opponents.

“Intimidation is an important part of sports,” he said on the radio. “People will try to intimidate you, if you back off you’re easier to beat. The game has a way of handling itself.”

Now we’re left to see how the rest of baseball responds.