This is what happens when baseball’s premier red-ass butts heads with one of the game’s loosest cannons. As if there wasn’t enough tension built in to St. Louis’ desperate chase of the Brewers in the waning days of the NL Central, Nyjer Morgan threw decorum—and his chew—to the winds Wednesday, shouting down Chris Carpenter as the Cardinals ace tried to finish a complete-game shutout.

This is what happens when baseball’s premier red-ass butts heads with one of the game’s loosest cannons. As if there wasn’t enough tension built in to St. Louis’ desperate chase of the Brewers in the waning days of the NL Central, Nyjer Morgan threw decorum—and his chew—to the winds Wednesday, shouting down Chris Carpenter as the Cardinals ace tried to finish a complete-game shutout.

After the right-hander struck out Morgan for the first out of the ninth inning, he directed an inflammatory comment toward the plate (at least according to Morgan), to which the hitter replied—and I lean here on my decades of experience reading lips via sports telecasts—“fuck you.” (Watch it here.)

Morgan, it seems, had been swiping at low-hanging fruit throughout the game, trying to rattle a pitcher who’s proved susceptible to such tactics in the past. To Carpenter’s credit, he didn’t cave.

“He was yelling at me at second base,” said the pitcher in an MLB.com report. “He was yelling at me down the line when he hit the double. The whole game he’s screaming and yelling, the whole game. I’m not going to allow it to happen. I don’t know if that’s the way he plays, to try to get guys out of their game or what. But I’ve been around too long to allow that to happen, I can tell you that much.”

As Morgan strode purposefully back to the dugout following his at-bat, he dismissively tossed his wad of chewing tobacco toward the mound. It didn’t come anywhere close to Carpenter, but that wasn’t Morgan’s intention. It was simply as dismissive a message as he could send in that moment.

Albert Pujols responded by charging in from first base, Prince Fielder raced to restrain Morgan, and the benches emptied. (No punches were thrown or shoves exchanged.) Morgan was eventually tossed by the umpires, at which point he could be heard on the telecast saying, “He said it first, he’s got to go, too.”

Were it only that simple. Morgan knows—and was likely trying to exploit—a history with the Cardinals that dates back to August, 2010, when the outfielder—then with Washington—went out of his way to senselessly collide with Cardinals catcher Bryan Anderson in a non-play at the plate.

That was followed this spring by an exchange that started when Morgan ran into Pujols in a play at first. Morgan and Carpenter got into a verbal spat during a series at Miller Park earlier this season. The teams also had tension over a tit-for-tat hit-batter exchange involving Pujols and Ryan Braun.

Ultimately, Morgan is either genuinely off-kilter or wildly canny, using the tactic of supreme annoyance to get his opponents off their collective game. (The former was bolstered by his recent run-in with fans in San Francisco. The latter has been ably demonstrated for years by A.J. Pierzynski.)

No matter the answer, it comes down to Nyjer being Nyjer. He said after the game that the confrontation “was over with”—but he wasn’t quite telling the truth.

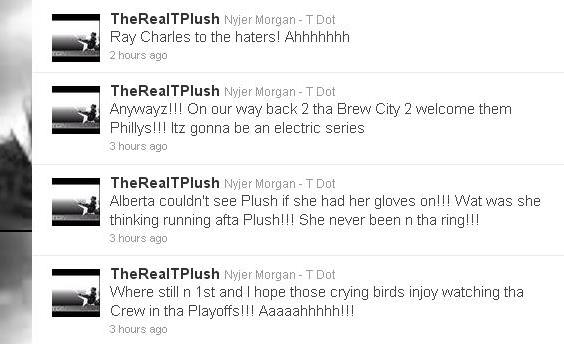

Not long afterward, Morgan sent out a series of tweets referring to Pujols as “Alberta” and saying “She never been n tha ring.” (See below.)

Ozzie Guillen once described Pierzynski this way: “If you play against him, you hate him. If you play with him, you hate him a little less.”

Through Morgan’s tenures in Pittsburgh and Washington, that appeared to be the case with him, as well. The Brewers, however, seem to love the guy.

He’d be well-advised to keep it that way.

Update: Morgan is headed in the wrong direction. Brewers management is not taking kindly to his act.

– Jason