If Brandon Phillips’ isn’t Jonathan Sanchez’s newest favorite person, he should be.

If Brandon Phillips’ isn’t Jonathan Sanchez’s newest favorite person, he should be.

Sanchez, the Giants’ No. 4 starter, let his mouth run loose on Sunday, when he guaranteed that his team would sweep its upcoming three-game series against San Diego and win the National League West.

Confidence is great, but braggadocio is rarely appreciated by one’s opponent. But just as pundits were beginning to dig into the concept of how to let sleeping dogs lie, Phillips laid down a distraction of such gravity that Sanchez may as well have forgotten how to speak English, for all the attention he’s getting.

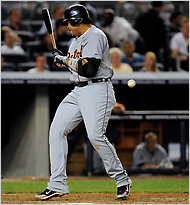

Turns out that Phillips doesn’t like the Cardinals. Like, even a little. Despite missing a recent game after fouling a ball off his leg, he was geared up for Cincinnati’s showdown with its NL Central rivals.

His full quote, as reported by Hal McCoy of the Dayton Daily News:

“I’d play against these guys with one leg. We have to beat these guys. I hate the Cardinals. All they do is bitch and moan about everything, all of them, they’re little bitches, all of ’em.

“I really hate the Cardinals. Compared to the Cardinals, I love the Chicago Cubs. Let me make this clear: I hate the Cardinals.”

- Fact: Phillips is a fun-loving guy.

- Fact: Phillips is a bit of a loose cannon.

- Probable fact: Phillips was merely joking around, and said what he did facetiously, in a light-hearted moment.

- Indisputable fact: None of that matters.

Earlier this season, Phillips claimed he meant no disrespect to the Washington Nationals when he beat his chest after scoring a run. It made no difference; he still got drilled in response.

Similar retaliation for Phillips’ recent statement is unlikely—his on-field act in Washington was met with an on-field response; this is a different matter entirely. Still, that hardly means the incident is over.

When David Cone publicly called out Dodgers pitcher Jay Howell in the 1988 NLCS, the Dodgers responded with a wave of bench jockeying so vicious that a rattled Cone lasted just two innings into his Game 2 start. (The story is outlined here, within the context of Carlos Zambrano’s calling out A’s pitcher Jerry Blevins earlier this season.)

Yesterday, the Cardinals let their pitching do their talking, as Phillips went 0-for-5 and struck out to end a 7-3 St. Louis victory that cut Cincinnati’s lead in the division to a single game.

Tony La Russa also got involved. Just as Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda amplified Cone’s quote to motivate his team in 1988, La Russa did his part to give Phillips’ statement some legs.

“We win the right way and we lose the right way,” he told reporters. “We’ve received a lot of compliments over the years that when we lose we tip our caps and when we win we keep our mouths shut. That’s my comment.”

Given a moment to think it over, however—in the post-game shower, no less—La Russa flagged down reporters and added this:

“I don’t think that will go over well in his own clubhouse. Phillips is ripping his teammates — Scott Rolen, Miguel Cairo, Russ Springer, Jim Edmonds—all the ex-Cardinals over there. He isn’t talking about this year. He is talking about the way we’ve always played and those guys are old Cardinals. Tell him he’s ripping his own teammates because they are all old Cardinals.”

If that’s the case, he’s doubly ripping the former Reds—Ryan Franklin, Jason LaRue, Kyle Lohse, Felipe Lopez, Aaron Miles and Dennys Reyes—in the St. Louis dugout.

The most vocal any Cardinals player got in response was to point to Phillips’ performance on the day, and reiterate that the game is played on the field, not in the media.

“I didn’t know we had bad blood,” Skip Schumaker said in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. “They can talk. And we’ll leave our comments to ourselves.”

It’s reminiscent of a similar dispute in 1972, when Angels pitcher Clyde Wright decided to talk about defending AL Cy Young and MVP winner Vida Blue, immediately after besting him in a 3-1 victory.

“Why should I be up for him?” Wright is quoted as saying in Ron Bergman’s book, Mustache Gang. “He’s just another pitcher now. I’m 8-3 and he’s 1-4. I can get up for the A’s, but not for Vida Blue. He doesn’t look as aggressive as before. You can see it in his eyes. He ran out to the mound, sure, but we all do that now.”

Blue’s response came eight days later, when he gave up a single run over nine innings to top Wright and the Angels. It was only then that he offered an opinion about what Wright had said.

“I don’t think Clyde Wright looked as aggressive as before,” Blue said after the game. “He ran out to the mound, but we all do that now. I can get up for the Angels, but not for Clyde Wright. What’s he now—8-4? I’m 2-4, but I’d say this even if I were 24-4.”

The Cardinals hardly needed motivation from Brandon Phillips to win the NL Central; how they perform down the stretch will be independent of anything he did or could say. (The same holds true for the Padres, in regard to Jonathan Sanchez.)

If they do pull it out, however, one sentiment pertaining to his statement will be irrefutably true: It didn’t hurt anybody but Cincinnati.

Update (Aug. 10): Talking about it today, Phillips didn’t back down, essentially saying that he said his piece, and now he just wants to win.

Reds manager Dusty Baker in McCoy’s column in the Dayton Daily News: “You prefer that they don’t say that, but everybody refers to the freedom of speech and then you say things and get in trouble for it. I talked to him about it and it just puts a little more pressure on him to play better personally.”

– Jason

Removing pitchers in the middle of no-hitters is getting to be downright commonplace these days.

Removing pitchers in the middle of no-hitters is getting to be downright commonplace these days.